Features

‘Proxy War Theories’ and misleading readings of global politics

Considering the present proliferation of views and opinions on the world’s raging conflicts, the importance of key commentators and observers of these developments having an in-depth knowledge of modern and even pre-modern world history cannot be stressed enough. This is on account of the fact that such a seeming lacuna in knowledge could lead to gross misinterpretations of these realties, which could in turn prove deleterious from the viewpoint of international peacemaking in particular.

Considering the present proliferation of views and opinions on the world’s raging conflicts, the importance of key commentators and observers of these developments having an in-depth knowledge of modern and even pre-modern world history cannot be stressed enough. This is on account of the fact that such a seeming lacuna in knowledge could lead to gross misinterpretations of these realties, which could in turn prove deleterious from the viewpoint of international peacemaking in particular.

One such opinion that shouldn’t go unexamined for its accuracy is the view that Israel’s current military operation against Hamas in the Gaza is a ‘proxy war’ being waged by Israel on behalf of the West, inclusive of the UK. A key proponent of this notion happens to be British Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch. In a recent interview the latter is quoted, for instance, as stating rhetorically: ‘Who funds Hamas? Iran – an enemy of this country. Israel is fighting a proxy war on behalf of the UK.’

To all outward appearances, Badenoch seems correct. Israel is indeed armed and funded to a degree by some key states of the West, principally the US, and is apparently fighting for the West’s interests against some the latter’s perceived international foes, such as Iran. But is Israel a mere Western proxy? Is it a glorified puppet, so to speak, in the hands of the West? These are questions of the first importance that cannot be ignored or glossed over in a discourse of this kind.

Here is where a thorough knowledge of modern Middle Eastern history becomes relevant. The UK was instrumental in setting up the state of Israel in the late forties during the latter stages of World War Two and it did right by doing so. As in the case of the Palestinians, the Israelis too were a displaced, ‘homeless’ people who needed a state of their own. Important sections of the West, inclusive of course the UK, empathized with Israel and this was perfectly in order since the latter were a brutally victimized people, particularly at the hands of Nazi Germany.

Accordingly, the Israelis deserved the empathy of not only the West at the time but also that of the rest of the world. Such empathy was not at all misplaced because Biblical history reveals, for example, that the Israelis enjoyed an independent existence as a community in the ancient world in the Middle Eastern region along with the Palestinians and other major ethno-religious groups before the Israelis were displaced and dispersed all over Europe by the then imperial powers, such as Egypt and Persia. Therefore, the Israelis had a right to a state, inasmuch as the Palestinians had a right to one.

Kemi Badenoch

However, once a state for the Israelis was established in the late forties, courtesy the UK and the West, violent ethno-politics on the part of Israel led to the latter acquiring more and more Palestinian land and this development eventually led to the current wasting war in the Middle East. Essentially, the task before the international community now is to help create two inviolable states where the Israelis and Palestinians could co-exist.

It doesn’t follow from the foregoing, though, that the Israel of today is waging a proxy war on behalf of the West, mechanically at the bidding of the latter, as it were. Considering the history of the Middle East conflict it is clear that Israel has to a great degree acted on its own with a profound interest is establishing a strong state of its own.

A peek into the history of the making of modern Israel by its founding fathers, such as first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion, would establish the veracity of the view that Israel has never been any external power’s obliging proxy, although it has been helped along by the West, in accordance with the latter’s prime interests.

For example, when sections of the West helped in establishing Israel, they did so with the expectation that Israel would act as a ‘policeman’ for them in the oil rich and strategically important Suez Canal region. Such motives persist to date.

In does not follow from the foregoing, though, that the Israel of today is justified in unleashing murderous violence on the Palestinians of the Gaza. Such wanton bloodshed must be brought to a halt and Israel needs to consider it to be in its vital interest to help work towards a political solution in the Middle East. If it does not do so, the security it is searching for would always remain elusive.

Badenoch and others of her ilk may be in error when they also characterize the conflict in the Ukraine as a proxy war, where Ukraine is said to be tamely serving the interests of the West. This too is a notable misreading of the war in the Ukraine.

What led to Ukraine going to war against Russia was the latter’s invasion of the former. It is primarily a question of Ukraine defending its sovereignty, which any self-respecting country in the same circumstances is bound to do. That the Ukraine is receiving the assistance of the West in its efforts is a matter of secondary importance.

However, from the West’s stand point it is doing right by assisting Ukraine because in terms of its fundamental values it is obliged to help a country whose sovereignty has been grossly violated by a big power whose political ideology is at variance with that of its own. We need to remind ourselves that the ‘New Cold War’ is at bottom a conflict of world views inasmuch as it is about military and economic power. It is by respecting each other’s rights and sovereignty that the world community could lay the basis for international stability.

Russia would do well to speak in earnest to the West about its security concerns rather than invade smaller neighbours who have long separated themselves from Russia as sovereign and independent states. It will be in the interests of the West to be sensitive to Russia’s security concerns because there could be no permanent peace in Europe as long as Russia believes its security is being compromised in some manner.

Features

India forcibly sterilised 8m men: One village remembers, 50 years later

When everybody ran, towards the jungles and nearby villages, or dived into a well to hide from government officials, Mohammad Deenu stayed put.

His village, Uttawar, in the Mewat region of northern India’s Haryana state, about 90km (56 miles) from the capital, New Delhi, was surrounded by the police on that cold night in November 1976. Their ask: men of fertile age must assemble in the village ground.

India was 17 months into its closest brush with dictatorship – a state of national emergency imposed by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, during which civil liberties were suspended. Thousands of political opponents were jailed without a trial, an otherwise rambunctious press was censored, and, backed by financial incentives from the World Bank and the United States, India embarked on a massive forced sterilisation programme.

Deenu and his 14 friends were among its targets. They were pushed into the forces’ vehicles and taken to ill-managed sterilisation camps. To Deenu, it was a “sacrifice” that saved the village and its future generations.

“When everyone was running to save themselves, some elders [of the village] realised that if no one is found, it would create even bigger, long-lasting troubles,” Deenu recalled, sitting on a torn wooden cot. “So, some men from the village were collected and given away.”

“We saved this village by our sacrifice. See around, the village is full of God’s children running around today,” he said, now in his late 90s.

As the world’s largest democracy marks 50 years since the imposition of the emergency on June 25, Deenu is the only man who had been targeted in Uttawar as part of the forced sterilisation project who is still alive.

More than 8 million men were forced to undergo a vasectomy during that period, which lasted until March 1977, when the state of emergency was lifted. This included 6 million men in just 1976. Nearly 2,000 people died in botched surgeries.

Five decades on, those scars live on in Uttawar.

![Mohammad Noor sitting with his childhood friend, Tajamul Mohammad, at his home in Uttawar, Haryana. [Yashraj Sharma/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Noor-Mohammad-with-Tajamul-1750790437.jpg?resize=770%2C578&quality=80)

‘A graveyard, just silence’

In 1952, just five years after securing its freedom from the British, India became the world’s first country to adopt a national family planning programme. At the time, the idea was to encourage families to have no more than two children.

By the 1960s, at a time when birth rates were close to six children per woman, the government of Indira Gandhi began adopting more aggressive measures. India’s booming population was seen as a burden on its economy, which grew at an average of 4 percent from the 1950s until the 1990s.

The West seemed to share that view: The World Bank loaned India $66m for sterilisation initiatives, and the US made food aid to a starving India contingent on its success at population control.

But it was during the emergency, with all the democratic checks and balances removed, that the Indira Gandhi government went into overdrive, using a mix of coercion and punishment to pressure government officials into implementing forced sterilisation, and communities into accepting it.

Government officials were given quotas of how many people they had to sterilise. Those who failed their targets had their salaries withheld or faced the threat of dismissal from their jobs. Meanwhile, irrigation water was cut off from villages that refused to cooperate.

Security forces were also unleashed on those who resisted – including in the village of Uttawar, which had a predominantly Muslim population, like many of the communities targeted. The Muslim birthrate in India at the time was significantly higher than that of other communities, making members of the religion a particular focus of the mass sterilisation initiative.

In the lane next to Deenu’s house, Mohammad Noor, then a 13-year-old, was sleeping in his father’s arms in a cot outside their house when policemen, some of them riding horses, raided their home. His father ran towards a nearby jungle, and Noor rushed inside.

“They broke the doors and everything that came in their way; they shattered everything they could see,” Noor recalled. “To make our lives worse, they mixed sand in flour. There was not even a single home in the village that could cook food for the next four days.”

Noor was picked up in the raid, taken to a local police station and beaten before he was let go. He said that because he was under 15, he was deemed too young for a vasectomy.

That night of scare, as the village calls it now, also gave birth to a local folklore: the words of Abdul Rehman, then the village head. “Outside our village, no one would remember this name, but we do,” said Tajamul Mohammad, Noor’s childhood friend. Both are now 63 years old.

Before raiding Uttawar, several officials had come to the village, asking Rehman to give away some men. “But he remained steadfast and denied them, saying, ‘I cannot put any family in this place’,” said Tajamul, with Noor nodding passionately. Rehman also did not agree to give away men from neighbouring areas either, who were sheltering in Uttawar.

According to a local Uttawar legend, Rehman told the officials: “I will not give away a dog from my area, and you are demanding humans from me. Never!”

But Rehman’s resolve could not save the village, which was left in a state of mourning after the raids, said Noor, sucking tobacco from a hookah.

“People who ran away, or those who were taken away by the police, did not return for weeks,” he said. “Uttawar was like a graveyard, just silence.”

In the years that followed, the impact became more visible and dreadful. Neighbouring villages would not allow marriages with men of Uttawar, even those who were not sterilised, while some broke their existing engagements.

“Some of the people [men in Uttawar] were never able to recover from that mental shock, and spent years of their lives anxious or disturbed,” said Kasim, a local social worker who goes by his first name. “The tension and the social taboo killed them and cut their lives short.”

Echoes in today’s India

Today, India no longer has a coercive population control programme, and the country’s fertility rate is now just more than two children per woman.

But the atmosphere of fear and intimidation that marked the emergency has returned in a new avatar, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, believe some experts.

For 75-year-old Shiv Visvanathan, a renowned Indian social scientist, the emergency helped perpetuate authoritarianism.

In the face of a rising student movement and a resurgent political opposition, the Allahabad High Court on June 12, 1975, found Indira Gandhi guilty of misusing state machinery to win the 1971 elections. The verdict disqualified her from holding elected office for six years. Thirteen days later, Gandhi declared a state of emergency.

“It was the banalisation of authoritarianism that created the emergency, with no moment of regret,” Visvanathan told Al Jazeera. “In fact, the emergency has created the emergencies that have followed in today’s India. It was the foundation of post-modern India.”

Indira Gandhi’s loyalists compared her with Hindu goddess Durga, and, in a play with phonetics, to India, the country itself, much like Modi’s supporters have compared the current prime minister with the the Hindu god Vishnu.

As the culture of the personality cult grew under Indira Gandhi, “the country lost the sense of understanding”, said Visvanathan. “With the emergency, authoritarianism became an instrument of governance.”

Visvanathan believes that even though the state of emergency was lifted in 1977, India has since slid towards complete authoritarianism. “All the way from Indira Gandhi up to Narendra Modi, each one of them contributed and created an authoritarian society while pretending to be a democracy.”

Since Modi came to power in 2014, India’s rankings have fallen swiftly on democratic indices and press freedom charts, due to the jailing of political dissidents and journalists as well as the imposition of curbs on speech.

Geeta Seshu, the cofounder of Free Speech Collective, a group that advocates for freedom of expression in India, said a similarity between the emergency years and today’s India lies in “the manner that mainstream media has caved in”.

“Then and now, the impact is felt in the denial of information to people,” she said. “Then, civil liberties were suspended by law, but today, the law has been weaponised. The fear and self-censorship prevalent then is being experienced today, despite no formal declaration of emergency.”

For Asim Ali, a political analyst, the defining legacy of the emergency “is how easily institutional checks melted away in the face of a determined and powerful executive leadership”.

But another of the emergency’s legacies is the successful backlash that followed, he said. Indira Gandhi and her Congress party were voted out of power in a landslide in 1977, as the opposition highlighted the government’s excesses – including the mass sterilisation drives – in its campaign pitch.

“Like the 1970s, whether Indian democracy is able to move beyond this phase and regenerate again after Modi remains to be seen,” Ali said.

![An elderly in Uttawar, who lived through the emergency years. [Yashraj Sharma/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Local-in-Uttawar-1750790376.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C578&quality=80)

‘Seven generations!’

Back in November 1976, Deenu said he only thought of his pregnant wife, Saleema, as he sat inside the police van while he was being taken away. Saleema was at home at the time.

“A lot of men, unmarried or childless, pleaded with the policemen to let them go,” Deenu recalled. None of Deenu’s 14 friends was let go. “Nasbandi ek aisa shrap hai jisne Uttawar ko tabse har raat pareshan kiya hai,” he said. (Sterilisation is a curse that has haunted Uttawar every night since.)

After eight days under police custody, Deenu was taken to a sterilisation camp in Palwal, the nearest town to Uttawar, where he was operated upon.

A month later, after he returned from the vasectomy, Saleema gave birth to their only child, a son.

Today, Deenu has three grandsons and several great-grandchildren.

“We are the ones who saved this village,” he said, grinning. “Otherwise, Indira would have lit this village on fire.”

In 2024, Saleema passed away after a prolonged illness. Deenu, meanwhile, revels in his longevity. He once used to play with his grandfather, and now plays with his great-grandchildren.

“Seven generations!” he said, sipping from his plastic cup of a bubbly cold drink. “How many people have you seen that enjoy this privilege?”

[Aljazeera]

Features

The best that never was: Sri Lanka-Japan Free Trade Agreement

A need for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Japan was proposed by the Sri Lankan exporters around 2010. At that time, Sri Lanka’s Department of Commerce, the main government agency responsible for the trade negotiations, also strongly favoured negotiating an FTA with Japan for a number of reasons.

The lack of a level playing field in Main Markets

By then, much of our export growth had come from two advanced economies; the European Union and the United States, which together accounted for more than half of our exports. In those markets, after the end of the quota arrangement for apparel exports, Sri Lanka’s competitiveness was getting eroded due to the absence of a level playing field. In the U.S. and EU, most of our competitors from Asia, Africa and the Americas were enjoying much better levels of market access through FTAs and other trade arrangements.

Our requests to Brussels and Washington for FTAs, since 2001, did not get any favourable response. In Washington, even after the U.S Administration turned down the request, the Sri Lankan embassy spent a large amount of money on consultants who promised FTA. But that too turned out to be simply a waste of money. After turning down the request for an FTA, Brussels offered an alternate arrangement to provide a better level of market access through GSP (labour), which was later upgraded to GSP Plus. But that too had run into problems by 2010.

The need for Market Diversification

Because of these developments, we at the Department of Commerce knew it was critically important to diversify our markets. In this regard, one of the most appropriate markets to focus on was Japan, the third largest developed country market and a sincere friend with close political and cultural ties with Sri Lanka, since independence. Japan was also closely involved in the post-conflict economic reconstruction activities to which she contributed generously. By 2010, Japan had concluded a number of FTAs with South East Asian countries.

These included, among others, Economic Partnership Agreements with Malaysia in 2006, Thailand in 2007 and Vietnam in 2009. Japan was also in negotiations for FTAs with a number of other countries, including India. In December 2005, Japan announced duty-free, quota-free (DFQF) market access to products from the least developed countries (LDCs). As a result, Asian LDCs were slowly increasing their exports to Japan. In addition to that, Japanese investors were also moving into those countries with enhanced market access. Consequently, Sri Lanka was becoming further marginalised in that important market.

Lanka proposes FTA with Japan

Then, in July 2010, a newspaper reported that Sri Lanka had proposed an FTA with Japan (“Lanka proposes FTA with Japan –Ready to consider, says Japanese Trade Minister”; Daily News 31 July 2010). According to this news report, a high-level ministerial delegation consisting of External Affairs Minister Prof G L Peiris and Economic Development Minister Basil Rajapaksa had visited Tokyo and had formally requested Japan to consider entering into a Free Trade Agreement with Sri Lanka and the Japanese Economy, Trade and industry Minister Masayuki Naoshima had responded to the request in cautiously positive manner and had reportedly stated that “The Government of Japan in keeping with the policy of Prime Minister Naoto Kan’s administration is prepared to engage in consultations with regard to a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Sri Lanka and Japan.

” After the delegation returned to Sri Lanka, the Department of Commerce was expecting a formal report on the ministerial discussions, to initiate the preparatory work for negotiations. After a few weeks, as we did not receive any reports on the meeting, we asked the Embassy in Tokyo for a report and also made inquiries from other government agencies. All that did not result in any meaningful response.

However, keeping to their words, Japan began to engage in an FTA. A short time later, the Japanese Embassy in Colombo arranged a presentation by a prominent Japanese academic on Japanese Free Trade Agreements. It was held at the Central Bank auditorium in Rajagiriya.

The night before that, the Japanese Ambassador organized a dinner at his residence for a selected group of senior Sri Lankan officials and academics to meet the visiting scholar. Among those present were the key official responsible for economic and financial matters of the country at that time and a professor who was also an economic advisor to the government. Through pre-dinner drinks, we discussed the impact of the FTAs on other Asian countries and the possibility of initiating FTA negotiations between the two countries. During the discussion, the professor strongly challenged the need for negotiating FTAs in general and one with Japan in particular.

Then the key official brusquely stated that “no one in Sri Lanka is interested in an FTA with Japan!” On the next day, during the presentation on the Japanese FTAs, senior officials of the Central Bank and the Finance ministry and many other relevant agencies were conspicuously absent. After that, it was difficult to move forward with that initiative any further.

A year later, in June 2011, Japanese Ambassador Kunio Takahashi met Minister of Industry and Commerce Rishad Bathiudeen and when the prospect of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Sri Lanka and Japan came under discussion, the ambassador very diplomatically responded by saying “The idea that an FTA with Japan will help Sri Lanka contribute to Lanka-Japan bilateral trade dialogue.” More important message on the FTA was conveyed to Mr Bathiudeen by the visiting Japanese Senior Vice Minister of Economy, Kazuyoshi Akaba in July 2014. That message was that “conclusion of FTAs alone is not sufficient for better trade. What is important is to develop a very robust foundation among the two countries”.

RW opts for FTAs with Singapore and Thailand

After the political changes in 2015, the Sri Lanka-Japan Business Co-operation Committee once again started to lobby for an FTA between Sri Lanka and Japan. Unfortunately, the government opted to negotiate an FTA with Singapore as a priority. After the change of government in 2019, prospects for an FTA totally diminished and almost totally evaporated after the unilateral cancellation of the $ 1.5 billion Japan-funded light rail transit project.

However, even after that, according to news reports, Katsuki Kotaro, Deputy Head of the Japanese Embassy in Colombo, has indicated that Japan may be interested in an FTA with Sri Lanka to increase bilateral trade between the two countries. But unfortunately, Ranil Wickremesinghe, who became the president in July 2022 and visited Japan in May 2023, didn’t take any initiative in this regard. Instead, he preferred to focus on an FTA with Thailand.

Lost Opportunity

It is difficult to understand why the government was reluctant to enter into consultations with Japan on an FTA during the last fifteen years, particularly because Japan was the only developed economy that responded favourably for an FTA, albeit with some reservations. But then it is more difficult to understand why the government unilaterally cancelled the $1.5 billion Japan-funded light rail transit project. It is also difficult to estimate the real cost for Sri Lanka from these decisions which were made by a small group of people. However, it is very clear that Sri Lanka certainly did not benefit from some of the initiatives the Japanese governments have taken in recent years, to help Asian countries.

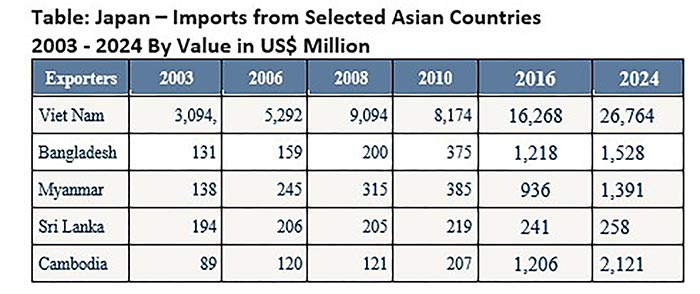

For example, the package of incentives extended to Japanese companies to shift production out of China. As a result, those investments went to other countries in the region and exports to Japan from those countries expanded significantly. The table below illustrates how some of our competitors in the region with export baskets similar to that of Sri Lanka; Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Myanmar, managed to expand their exports during the last fifteen years. (See Table)

In 2003, exports to Japan from Sri Lanka (US$194 million) were much more than those from Cambodia (US$ 89 million), Myanmar ($138 million) or Bangladesh (US$131 million). But exports from those countries have expanded significantly since 2010 due to the trade and economic policies those countries adopted.

Cambodia’s exports to Japan increased from 89 million in 2003 to US$ 2.1 billion by 2024. Sri Lanka’s exports increased only from US$194 million to US$ 258 million during the same period. Bangladesh’s exports crossed the US $1.5 billion mark in 2024. That was from US$131 million in 2003. This explains how much Sri Lanka suffered due to bad decisions made by few individuals.

To add insult to injury, since 2022, Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka has a shiny new Metro Rail System, a project largely funded by Japan. Colombo’s Japanese-funded Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project was to be completed mid-2024. Unfortunately, both the FTA and LRT were sabotaged by a few of our key decision makers.

(The writer, a retired public servant and a diplomat, was the Director General of Commerce from July 2009 to November 2011. He can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

by Gomi Senadhira

Features

Stamping on Science: Dr. Anslem de Silva and team expose global philatelic fraud featuring Sri Lankan snake art

In an unexpected twist that links science, conservation, and global fraud, Sri Lanka’s leading herpetologist Dr. Anslem de Silva has found himself confronting a unique kind of biological piracy—this time, not in the jungles, but on postage stamps.

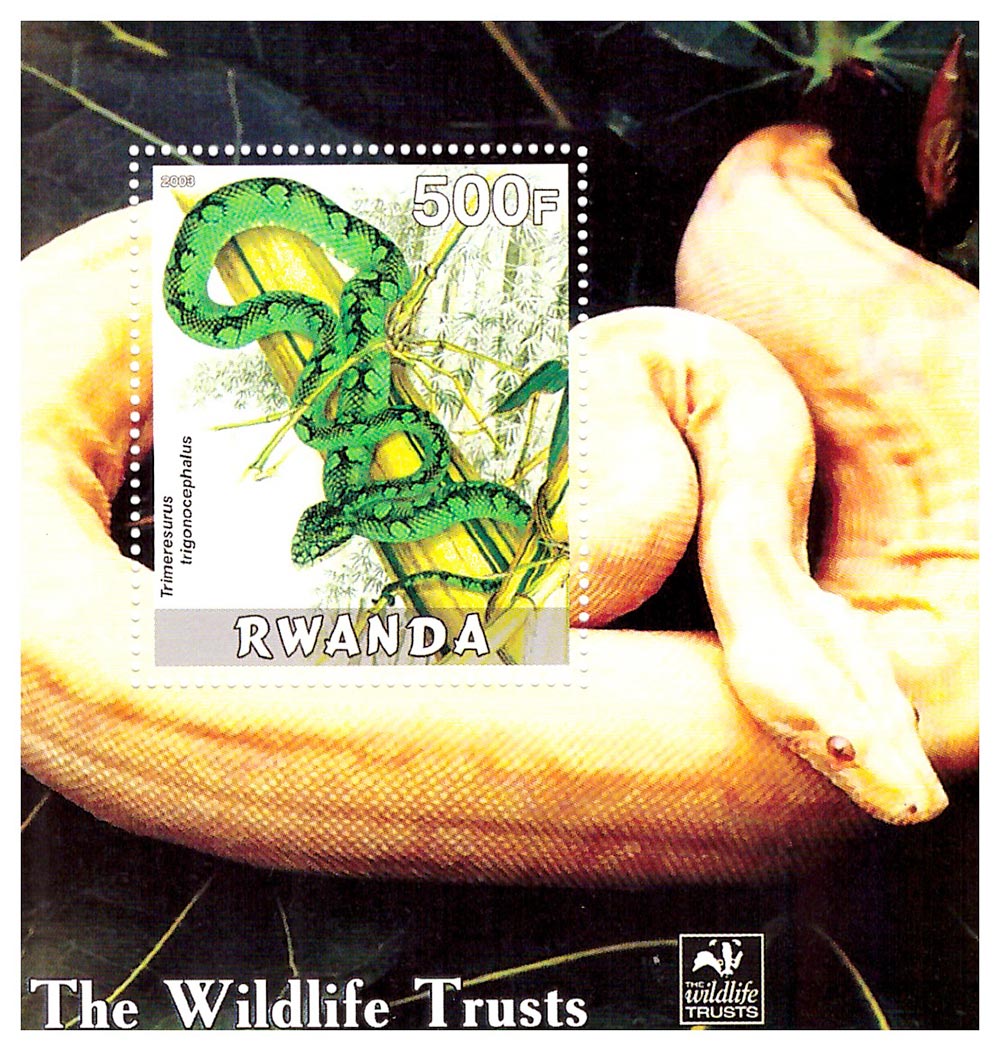

A world authority on reptiles and amphibians, Dr. de Silva, along with Malaysian biodiversity expert Prof. Indraneil Das and wildlife artist Jayantha Jinasena, has uncovered a series of counterfeit Rwandan stamps illegally showcasing hand-drawn illustrations of snakes endemic to Sri Lanka.

Published as a scientific note, the team’s exposé titled “Illegal Philatelic Issues in the Name of the Republic of Rwanda, Depicting Sri Lankan Snake Images” documents how a probable Eastern European agency falsely issued philatelic materials under Rwanda’s name. These unauthorized “stamps” bear not only the likenesses of rare Sri Lankan reptiles but also plagiarized images painted by Jinasena, originally published with scientific accuracy and artistic sensitivity.

“This was not just a violation of copyright,” said Dr. Anslem de Silva in an exclusive interview with The Island. “It was an assault on science, conservation, and our national biodiversity identity.”

Dr. Anslem de Silva, recipient of numerous national and international awards including the Presidential Award for Science, is known as the “father of herpetology in Sri Lanka.” Based in Gampola, he has authored over 400 scientific papers and numerous books, most notably Snakes of Sri Lanka: A Coloured Atlas (2009), a seminal reference on the island’s serpentine diversity.

He collaborated on this investigation with Professor Indraneil Das, a leading Malaysian herpetologist and academic at the Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. Prof. Das is globally respected for his work on reptiles and amphibians across Asia and has published over a dozen scholarly books.

The third member of the team, Jayantha Jinasena, is an acclaimed Sri Lankan naturalist and wildlife illustrator. His highly detailed watercolour renderings of reptiles are widely recognised in academic and conservation circles. Many of the stolen images in question were initially hosted on Jinasena’s personal website and later published in his 1998 portfolio Snake Man and in de Silva’s 2009 volume.

The counterfeit stamps first surfaced online on April 1, 2003—coincidentally, All Fool’s Day. The team discovered two specific philatelic items marketed under Rwanda’s name: a miniature sheet featuring a single image of Trimeresurus trigonocephalus (the Sri Lankan Green Pit Viper) and a souvenir sheet with six images of endemic snakes, including Hypnale hypnale, Xenochrophis piscator, and Aspidura trachyprocta.

What raised eyebrows was that not one of these species is native to Rwanda or even to the African continent. In fact, they are exclusively found in Sri Lanka, and several of the images had been altered—flipped or printed upside down—displaying clear biological ignorance by the counterfeiters.

Moreover, both sheets bore the logo of The Wildlife Trusts, a UK-based conservation charity. The stamps’ design featured the Trusts’ branding and their European Badger emblem, misleading buyers into believing they were part of an international conservation-themed issue.

- Souvenir sheet with six images of endemic snakes, including Hypnale hypnale, Xenochrophis piscator, and Aspidura trachyprocta.

- Trimeresurus trigonocephalus, featured on the counterfeit miniature stamp, is endemic to Sri Lanka and not found anywhere else in the world.

Dr. de Silva reached out to The Wildlife Trusts for clarification. Belinda Grindrod, a representative of the UK charity, swiftly responded, stating the organisation had no knowledge of such stamps and confirmed that it does not operate outside the UK. She clarified that any legitimate stamp bearing their brand would have been a UK issue—if at all—and certainly not one issued in the name of Rwanda.

Prof. Indraneil Das, whose decades-long research focuses on the taxonomy and conservation of amphibians and reptiles, called the act “a damaging example of how biodiversity knowledge can be misappropriated for unethical commercial gain.’ Speaking from his lab in Malaysia, he added, “When science and conservation art are stolen in this way, it not only breaches copyright—it erodes public trust and distorts the narrative around global biodiversity.’

The team also highlighted the economic ramifications. The stamps are sold online for as little as USD 1for the miniature sheet and up to USD 4 for the souvenir sheet. Alarmingly, some were marketed as “postally used,” complete with counterfeit cancellation marks bearing the word “Rwanda.” However, real postal cancellations indicate specific post offices—not countries—raising further suspicion.

Concerned by the damage to its international image, the Rwandan postal authority formally wrote to the Universal Postal Union (UPU)—the UN agency that regulates global mail operations—condemning the counterfeit stamps. In its circular dated October 13, 2003, Rwanda’s postal service emphasized that:

“Unidentified, unscrupulous individuals are seeking to discredit our country by circulating postage stamps that they claim have been issued by Rwanda… We deplore this usurpation of our rights and condemn these shameful actions.”

The circular went on to appeal to other UPU members and philatelic bodies worldwide to support Rwanda in combating this fraudulent activity.

Rwanda clarified that it has no philatelic representatives outside its territory, urging collectors to verify authenticity directly with the National Post Office in Kigali.

A Larger Threat to Biodiversity and Philately

These illegal issues—referred to as “Cinderella stamps” in philatelic terms—are not just niche concerns. According to John Mackay, a leading authority on stamp forgery, Cinderellas can include anything resembling a stamp but not officially issued for postal use. These are often omitted from established catalogues like Stanley Gibbons and Scott.

According to stamp crime experts Pocock (1999) and Winick (2002), such forgeries can become tools of money laundering, organized crime, and illicit trade—given that stamps are easily convertible and collectible globally.

To counter this, the World Association for the Development of Philately and the UPU created the World Numbering System (WNS) in 2002. This digital platform lists officially recognized stamps from UPU member countries. Unfortunately, not all postal authorities participate, leaving gaps that counterfeiters exploit.

- Arabian sea snake

- Annulated sea snake

- Ornate flying snake

Beyond Stamps: Protecting Intellectual and Ecological Heritage

For Dr. de Silva, the incident underscores the urgent need to protect scientific illustrations and conservation art from global exploitation. “These aren’t just pictures,” he explains. “They are educational tools used in awareness campaigns, school materials, biodiversity databases, and policy documents.”

He also sees this as a warning for governments and academic institutions in the Global South. “We often don’t have the legal muscle or funding to pursue international copyright cases. But that doesn’t mean our knowledge systems are fair game.”

Jayantha Jinasena, the artist whose paintings were misused, echoed this frustration. ‘It’s not just about me. It’s about misrepresenting Sri Lanka’s natural history on an international platform. Our native species were wrongly portrayed, wrongly credited, and wrongly sold.’

The scientific trio has called for a multi-pronged response:

Awareness among collectors to avoid buying unverified stamps.

Tighter international oversight by postal and philatelic bodies.

Legal reform in biodiversity-rich countries to safeguard illustrations and scientific data.

They also urge universities, museums, and NGOs to watermark or digitally tag artworks to prevent future theft.

Dr. de Silva believes this is only the tip of the iceberg. “What happened to Sri Lankan snakes could happen next to Amazonian frogs or Himalayan birds. It’s time the global conservation and postal community took this seriously.”

In an era where images spread faster than truths, this case reminds us that even something as small as a postage stamp can hold global consequences. Thanks to the vigilance of Dr. Anslem de Silva and his team, a rare herpetological crime has been exposed—one that shows how closely intertwined science, art, and ethics truly are.

Sri Lanka’s snakes, carefully studied and beautifully illustrated, deserve to be known for their biological wonder—not as victims of an international scam.

Trimeresurus trigonocephalus, featured on the counterfeit miniature stamp, is endemic to Sri Lanka.

The Wildlife Trusts, wrongly named on the stamps, is the UK’s largest environmental NGO, with no operations outside the British Isles.Some counterfeit stamps are so well-designed they pass as real—unless scrutinized by philatelic experts.

By Ifham Nizam

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoKaspersky 1Q 2025 insights reveal impact of local and global servers on Sri Lanka’s cybersecurity

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSDB bank and Australia’s Market Development Facility partner to strengthen coconut, coffee and mango value chains

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoGreat teacher and historian of Navy:

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoSL Ambassador to Austria emphasises Sri Lanka’s emergence as a South Asian innovation hub

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLankan Embassy in Holland hosts online dialogue to strengthen ICT collaboration

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCeylon Bank Employees’ Union threatens strike over unresolved issues

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoHow Premadasa’s ill-conceived strategies undermined Wanasinghe’s Army

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBus operators in overdrive to knock down fare reduction