The moment that made me quit drinking happened on Sunday, May 8, 2022 — Mother’s Day. My wife, our 9-month-old, and I were having lunch at a North London restaurant my cousin had recommended. I was euphorically inebriated, repeating aloud the word wow throughout the meal. The sourdough with brown butter was a golden cloud of creamy warmth. The hake and Tokyo turnip melted and crackled in its Parmesan–and–black-pepper sauce. The tarte Tatin with fennel-seed custard sang to me in layers: spiced, silken, and slow. My wife’s and son’s faces were heart-swellingly beautiful — Wow, oh, wow. When I looked out the window behind them, the sunshine was the brightest I’d ever seen without being at all harsh. I could see the souls of everything. Buildings, cars, trees, cyclists lit from within, vivid but soft around the edges. That same bright, safe, warm vibrancy shone in me, too.

But the universal harmony was fractured suddenly by what felt like a blow to my head. Our son was banging the blunt end of his fork against the table. The clamor of it was impossibly loud and intrusive; it ripped me out of my bliss and sent a headache flashing through my skull. He seemed amazed by the powerful sound he could make with this giant, shiny tool. Now squinting from the glaring sunlight, I gently begged him to stop. When he didn’t, I asked my wife to help since she was next to him. She tried with lackluster conviction, not actually removing the fork from his small hand. She shrugged.

In that ten-second span, the world transformed from a radiant, expansive paradise to a war zone without allies. Pressure built rapidly, filling my torso, pushing for a way to break out and strike at the two people I love most in the world.

Luckily, the fuming anger dissipated as quickly as it had risen. I was too stunned by the force of my rage to be at risk of actually harming anyone in that moment. What rushed in next was the pain and fear of two childhoods — mine and the one I feared awaits my son — misshapen by a chronically dysregulated parent. A parent who screams, withdraws, adores unpredictably, and eventually resorts to violence. Being faced with the danger I posed to my son was the most sobering moment of my adult life.

So that was the last time I drank. It wasn’t the hundreds of fights or the thousands of depressions. It wasn’t two weeks earlier when the police escorted me home in the middle of the day for apparently shouting at people in the park to go kill themselves (I mostly remember being delirious with laughter at how young the officers looked in their ill-fitting uniforms and custodian helmets, children playing dress-up). It wasn’t even all the puking. If I had to guess, I’d say I vomited about two or three times a month from the ages of 15 to 38. It was that day, that moment, seeing my son for the first time in the crosshairs of my fight response that caused the shift.

I was shocked a lot as a kid. Some combination of the volatility at home and my being highly sensitive. I coped through hypervigilance, tiptoeing into the kitchen to survey the atmosphere before revealing my presence; through numbing, drinking Screwdrivers when I got home from school in fifth grade and huffing my sister’s inhaler until I spun and floated away; and, eventually, through expressions of anger, raising my voice first.

Even now, the tinging of heating pipes can make me jump. Strangers who don’t make room for others to pass on the sidewalk can spark violent rage, albeit toxically contained. Small miscommunications can carry the stakes of “destroy or be destroyed.” Being ignored can trigger anxious attachment responses. Unpredictable moods swing from a fury that has me pacing and mumbling rehearsed, vitriolic fantasy arguments with people to despondent lows marked by slumping immobility. These adaptive behaviors were intended to protect me and make sense of my world when I was a boy. As a man, I find they can easily turn destructive.

One of my closest friends, Arthur, told me more than once that the peace, the groundedness, I’m looking for starts with listening to the sensations in my body. He said this after I admitted I struggled to meditate or to sit in a still bath because it was too frightening to hear my own heartbeat. After quitting drinking — and consuming books, articles, podcasts on addiction, and recovery meetings with the same obsessiveness as I once drank — I wanted to feel all my feelings, not just the pleasurable ones. I was ready to connect my head to my body. I found a somatic therapist and an embodied-dance practice. Dancing sober as a middle-aged man was the first time I felt true self-love.

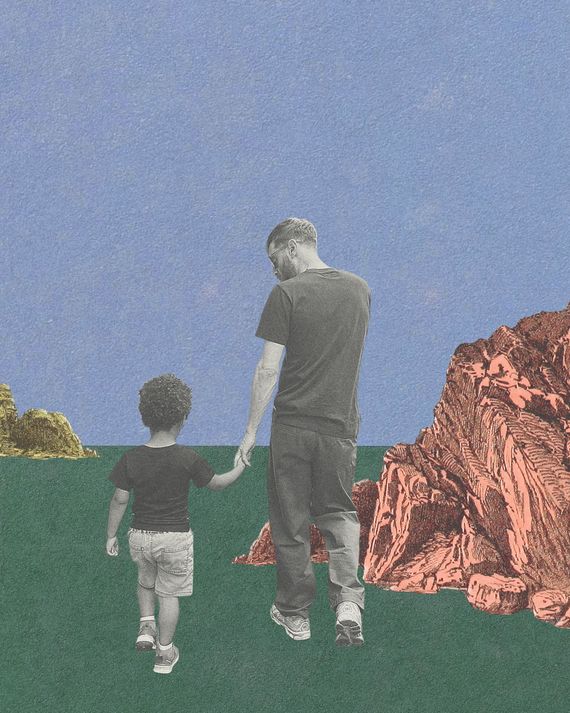

I have a fantasy now of going to my embodied-dance classes with my son when he’s older. I would get to witness him meeting, accepting, and expressing his deepest and most natural physical impulses safely and without constraint. I’m not overly attached to this fantasy, though. One thing I’m proud of is how little I see him as belonging to me. It’s surprising because I know possessiveness resides in me and I have felt its underlying desperation surface in relationships before. But I think the heart of that fantasy is about being together while being wholly independent.

Even with all the resources I’ve collected and surrounded myself with — my somatic therapy, dance, empathy, writing, SSRIs, supportive relationships, a loving partner — I remain in delicate balance.

As I write that last sentence, my son comes into the office. He’s 3 and a half now.

“Baba, I’m eating yogurt and nuts with Mama!”

“Yeah, is it good?”

“Yeah. What are you doing?”

“I’m writing.”

“About what?”

“About my problems, I guess. The ones that might affect you.”

“Where were you when that happened?”

“I was all over. Do you think you’d want to read about it someday?”

“Yeah,” he nods. “When I’m older, okay, Baba?”

He slowly backs out of the room and closes the door.

He has great instincts. And humor. That smile, that giggle, that uncanny comedic timing. Earlier, he’d delivered one of his best recurring bits: He farted, looked me dead in the eye, and said, “I’m going to tell Mama that was you.” I’m confident he has empathy, too; he’s so moved by other people’s pain and joy. In bed the night before, he said he was sad because he’d said something mean to his mama earlier. I asked if he wanted to talk to her about it. He said “yes,” and they did that. I also know he’s cultivating self-awareness. Sometimes, when he’s in the middle of a meltdown (say, over the wrong color socks), his screaming and crying will transition into screaming and crying about how he can’t seem to stop screaming and crying. He verbalizes his own loss of control in the middle of its chaos. It strikes me as an advanced level of self-reflection even among adults.

What I fear he lacks is what I’m not sure I can provide. When he gets that crazed look when screen time ends, I worry he shares my addictive traits. When he resists going to his swimming lessons, I worry he has my lack of perseverance. When someone greets him and he doesn’t reply, I worry he has my dissonant freeze response. And when he’s perfectly content to wrestle and dance with me in the living room for hours to Fela Kuti or LCD Soundsystem, I worry I’m depriving him of community.

I feel acutely that the lack of community in my life is a missing puzzle piece, yet I still observe myself approaching groups with suspicion. Something as simple as a group of likable colleagues asking me to grab a bite after work or getting invited to socialize after one of my beloved dance classes inspires a tug to get out of it somehow. It’s as if I have to leave before getting stuck, before I’m indebted, before I belong to them. Or before I fail. Before I’m left, before I’m rejected, before I’m unwanted.

My son interrupts my writing again as I’m thinking about this.

“Baba! Come out here and watch what I can do with this!” He has a plastic frog that jumps when touched.

“I’m busy now, can you show me later?”

“Okay, one minute. Set the alarm.” I smiled at his use of my own method against me.

I respond the way he usually does, “No, 40 minutes.”

He finds this hilarious. “No, two minutes!”

“Five.”

“Two.”

“Four.”

“Two.”

“Three.”

“Two.”

“No, three.”

“No, two.”

This could go on forever, so I say “okay” and set the alarm for three. He shuts the door behind him, and I sit with the irony of getting rid of him so I can write about my relationship with him.

His simple presence has decentered core aspects of my identity. When he had COVID at 5 months and I ran to the hospital with him in my arms, his eyes rolling back, my only thought upon seeing the crowd waiting to get inside was How do I get in front of them? If no one had told us children can skip the line, I would have cut anyway. An essential value — that all lives have equal worth — easily collapsed in the face of what proved to be a relatively mild health event. None of those other lives mattered then. Once inside, the medical team asked if I could switch places with my partner (COVID rules allowed only one parent) since I was shouting everything. I loudly refused.

He may not belong to me, but he is, paradoxically, an extension of my self-preservation. When he’s hurting, I’m hurting. I don’t say that with pride. I know the extent to which I identify with his suffering, real and imagined, has the potential to be unhealthy, drawing out something in me that could do more harm than good.

He has initiated the deconstruction of so many parts of myself. It has made me more aware of the tactics those parts developed to confront the world and the wounds beneath that prompted them. More than writing this for my son, I’m writing it thanks to him — and to thank him:

It’s thanks to you that I’m learning to speak and write on behalf of the pain these parts carry, rather than through them; to see how young and trapped in old survival loops they are; and how, in order to heal, they must be welcomed and treated with compassion, even gratitude for their commitment to protecting me, but not be allowed to drive anymore. It sounds simple and obvious to me now (like most of my greatest personal insights), but just acknowledging that the part of me that feels angry or afraid is separate from my whole self, rather than letting that part govern my perspective and behavior, was a breakthrough.

We all have to live with our parents’ problems in some form or another. I just want you, my son, to only have to live next to, not inside of, mine. So far, I’ve never truly lost it with you. But I have gone cold and unsmiling. I have said “no” to you much more than necessary, out of an anxious, control-seeking instinct. I have been rigid when softness and humor would have been more effective, more reassuring. Each impatience feels like a failure. Other parents say it’s normal. Maybe it even helps kids see their parents as human. Maybe.

And maybe my fear of passing down internal volatility is what saves you. Or maybe it’s a red herring that distracts from your real challenges. Talking about it seems like a necessary part of the protection plan.

I’m 41 now, old enough to know that if I were to look at this in a year, a fair amount of it will feel naïve and embarrassing. If I’m lucky, I’ll see it as an endearing marker of where I was as a younger dad, like a bad tattoo. But my hope is that if I name these concerns and projections as they evolve, you and I will more easily see how they’re separate from you. That the more understanding there is between us, the more it will mitigate your inheritance of my issues. That we’ll find ways for my baggage not to weigh on you. I can’t say for sure if that’s how it’ll work. But it’s my best idea for now.

You come into my office one last time:

“Baba, look at this,” you say, showing me how you tied a red pipe cleaner around a wooden spoon. “You’re still writing?”

I put you on my lap. You suck your thumb and stare at the strings of letters. “Do you have as many problems as —?” you ask, naming one of your classmates.

“Probably a lot more. But different kinds. You know, everyone and their father have problems,” I explain.

You press your hand to the keyboard, hitting random keys. I want to say, “No, don’t touch the computer.” But I let the impulse float by, feeling proud of that small release of rigidity. I watch you bang on the keys for a bit, and I can feel your excitement at the permission you’ve been given, at my letting you in, allowing you to follow your natural impulses.

I kiss the back of your head. You say, “I’m writing, Baba. I’m writing problems. Please don’t disturb me, okay?”

“I’ll try not to, my love.”