On 14 June 1941, the Soviet Union deported more than 10,000 people from Estonia to Siberia, in one of the darkest chapters of the country’s history – among them were over 7,000 women, children and the elderly; the date is now marked annually as a national day of mourning.*

In the summer of 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as a result of the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on 23 August 1939. As a result of the Second World War, Estonia lost about 17.5% of its population.

The Soviet occupation ushered in an event previously known only from the pages of history books – an event that became one of the most harrowing memories of the past centuries: the mass deportations, which affected people of all nationalities living in Estonia. The two deportations that left the deepest scars – on 14 June 1941 and 25 March 1949 – are commemorated annually as national days of mourning.

Prologue to the deportations of the 1940s

On 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact – a non-aggression treaty whose secret protocols carved Central and Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Just days later, on 1 September, Germany invaded Poland, unleashing the Second World War.

On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union – honouring its secret agreement with Nazi Germany – invaded Poland from the east, even as it amassed significant military forces along the borders of the three Baltic states and Finland. Although the Estonian government had declared its neutrality at the outbreak of the Second World War, it was left with little room to manoeuvre. On 28 September, under the threat of military force, Estonia was compelled to sign a so-called mutual assistance pact with the Soviet Union, paving the way for the establishment of Soviet military bases on Estonian soil.

Similar treaties were also imposed on Estonia’s southern neighbours, Latvia and Lithuania, under equally coercive circumstances. The gravity of Soviet pressure was laid bare when Finland, unlike the Baltic states, refused to sign such an agreement. In response, the Soviet Union launched a full-scale invasion – what became known as the Winter War. The international community condemned the aggression, and the USSR was expelled from the League of Nations. Yet this symbolic act had little, if any, impact on Soviet ambitions or policy.

In the summer of 1940, the Soviet Union occupied and forcibly annexed Estonia, together with Latvia and Lithuania, acting in accordance with the secret protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Moscow seized the opportunity at a moment when the world’s attention was fixed on the unfolding catastrophe in France, exploiting the turmoil of war in Western Europe to tighten its grip on the Baltic states.

At the behest of the Soviet authorities, sham parliamentary elections were staged across the Baltic states, with results falsified to create a veneer of legitimacy. These elections were condemned and never recognised by the democratic Western powers.

Almost immediately, the Soviet regime launched a brutal campaign of repression in Estonia, extending even to ethnic minorities such as Jews and Russians. Particular emphasis was placed on dismantling the country’s cultural, economic, political and military elite – an orchestrated attempt to erase the foundations of the independent Estonian state.

During the war, Nazi Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union and occupied Estonia from July 1941 until September 1944. Following the German retreat, the Soviet Union swiftly reasserted its control, re-establishing its occupation of Estonia.

Preparations for repressions

Even before the occupation of Estonia, the Soviet Union had begun laying the groundwork for a campaign of terror against Estonian civil society. As in other occupied territories, the goal of this communist repression was clear: to crush any potential resistance from the outset and to instil such profound fear in the population that the emergence of any future organised opposition would be all but impossible.

In Estonia, the deliberate targeting of prominent and active individuals, alongside the mass expulsion of entire social groups, was designed to dismantle the very fabric of Estonian society and cripple its economy. The lists of those marked for repression had been compiled well in advance. Archival records of the Soviet security services reveal that as early as the 1930s, detailed information was being gathered on individuals who would later be subjected to arrest, deportation or execution – part of a long-planned strategy to erase national identity and quash any potential opposition.

According to instructions issued in 1941, those marked for repression in the territories to be annexed by the Soviet Union – including Estonia – comprised a wide and varied cross-section of society. Targeted individuals, along with their family members, included all former government members, senior state officials and judges, high-ranking military officers, former politicians, members of voluntary national defence organisations and student associations, as well as those who had taken part in anti-Soviet armed resistance.

Also listed were Russian émigrés, members of the security police and police officers, representatives of foreign companies, individuals with any foreign contacts, entrepreneurs, bankers, clergymen and even members of the Red Cross. The aim was total societal control through the systematic elimination of anyone deemed ideologically or politically undesirable.

Approximately 23 per cent of the population fell into these targeted categories. In practice, however, the number of those subjected to repression was significantly higher, as many individuals who were not officially listed also became victims – often as a result of personal denunciations, arbitrary decisions or broader efforts to instil fear through indiscriminate persecution.

The Soviet security organs began their repressive activities in Estonia even before the country’s formal annexation. Following the occupation in June 1940, politically motivated arrests commenced almost immediately, marking the start of a campaign of intimidation and control. From that point onwards, the number of arrests steadily escalated, setting the stage for the mass terror that would soon engulf the nation.

On 17 July 1940, the last Commander-in-Chief of the Estonian Defence Forces, General Johan Laidoner, and his wife were deported to Penza. Just weeks later, on 30 July, President Konstantin Päts and his family were exiled to Ufa. Both men –central figures in Estonia’s struggle for independence – died in Soviet captivity, their fates emblematic of the regime’s ruthless dismantling of the Estonian state.

Mass deportations begin

Preparations for the mass deportations began no later than 1940 and formed part of the broader campaign of violence unleashed across the territories occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939–1940. The first to suffer were the Ukrainian and Belarusian regions, where mass deportations served as a grim prelude to what would later unfold in the Baltic states.

The earliest known written reference to the planned exile of Estonians to Siberia appears in the papers of Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin’s trusted commissar who orchestrated the dismantling of Estonia’s independence in the summer of 1940. In a report to the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in the autumn of that year, Moscow’s representative in Estonia, Vladimir Bochkaryov, called for the expulsion of the so-called “anti-Soviet element” from the territory of the newly formed Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic. It was a chilling foreshadowing of the mass deportations that would soon follow.

Concrete preparations for the mass deportations began in the winter of 1940–1941. On 14 May 1941, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party, together with the Council of People’s Commissars of the Soviet Union, issued a top-secret directive entitled Directive on the Deportation of the Socially Alien Element from the Baltic Republics, Western Ukraine, Western Belorussia and Moldavia. This classified order laid the administrative and logistical groundwork for one of the most far-reaching acts of repression in Soviet-occupied Europe.

14 June 1941

The first wave of deportations began in the dead of night –between 13 and 14 June 1941. Families who had gone to bed on a quiet Friday evening, unaware of the terror about to descend, were jolted awake in the early hours by loud banging at their doors.

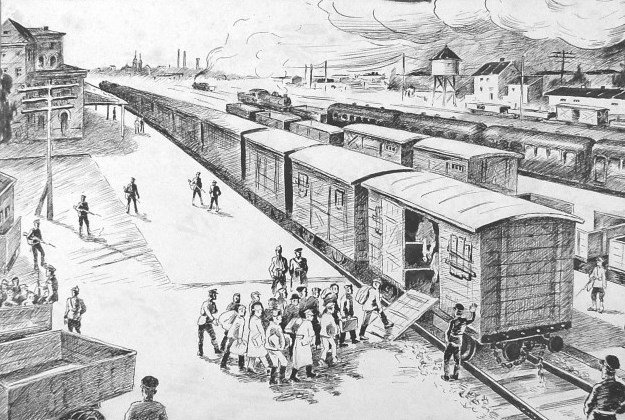

NKVD officers, often accompanied by local collaborators, read out decrees informing residents that they were under arrest or subject to immediate deportation – without trial, without explanation, and without recourse. All personal property was declared confiscated. The families were given just one hour to pack what they could carry before being loaded onto waiting lorries, bound for the cattle wagons that would take them east.

Just hours after the first knock on the door, the lorries began arriving at railway sidings across the country. A total of 490 cattle wagons had been reserved for the operation.

The search for those marked for arrest or deportation continued relentlessly until the morning of 16 June. The deportations were carried out with chilling brutality. Pregnant women, small children, and the seriously ill – including elderly people barely able to stand – were all herded into the same overcrowded, unsanitary wagons, with no regard for their condition or fate.

According to an order issued from Moscow on 13 June, more than 10,000 people were deported from Estonia between 14 and 17 June 1941. Among them were over 7,000 women, children and elderly individuals.

The sheer scale of the operation is underscored by a harrowing statistic: more than a quarter of those deported in June 1941 were minors – children under the age of 16. It was a systematic act of state violence that tore families apart and traumatised an entire generation.

The deportations also dealt a heavy blow to Estonia’s Jewish community. More than 400 Estonian Jews – around 10 per cent of the country’s Jewish population at the time – were among those forcibly removed.

As the first trains carrying deportees reached their distant and often deadly destinations, preparations were already underway for a second wave of deportations orchestrated by the Soviet authorities in Estonia. However, the course of history intervened.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 – just days after the initial deportations – halted the broader operation. Owing to the rapid advance of the front, only the island of Saaremaa saw a second round of deportations before Soviet forces were forced to retreat.

By the end of 1941, Soviet investigative commissions began operating within the prison camps, carrying out on-site interrogations and handing down swift, often arbitrary verdicts. These resulted in the execution of hundreds of prisoners.

By the spring of 1942, of the more than 3,000 Estonian men deported to the camps, only a few hundred were still alive. The rest had perished through a combination of executions, forced labour, starvation and disease – victims of a system designed not merely to punish, but to eliminate.

The fate of the women and children deported to the remote regions of the Kirov and Novosibirsk oblasts was equally harrowing. Exposed to extreme cold, chronic hunger and relentless forced labour, many perished in the harsh conditions.

Of the more than 10,000 Estonians deported in June 1941, only 4,331 – less than half – ever returned home. The 1941 deportations formed part of a vast operation across Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe: in the space of just one week, around 95,000 people from Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Bessarabia (modern-day Moldova) were deported to the interior of the Soviet Union.

Witnessing the harsh fate of the deportees

The harsh fate of the deportees is preserved in numerous memoirs and archival documents, offering a deeply personal lens through which to understand the trauma. Among the most poignant is the diary of ten-year-old Rein Vare, written between 1941 and 1944. His entries chronicle the journey into Siberian exile and the daily struggles of survival – offering a child’s unflinching account of cold, hunger, loss and endurance under Soviet repression.

With haunting maturity, Rein Vare illustrated his diary with grave markers for the playmates he had lost – small lives claimed by exile. Much of the diary is devoted to his beloved father, also named Rein Vare, the schoolmaster of the village of Sausti in northern Estonia. Though he had already died of starvation in the Isaroskino prison camp, he remained very much alive in his son’s writings – an enduring presence in a world that had otherwise collapsed.

A glimmer of hope returned in 1946, when Rein and his sister were finally permitted to return to their relatives in Estonia. The news stirred overwhelming emotion in their mother, who, driven by an unbearable longing for her children, made a desperate attempt to follow them. Abandoning her place of exile in Siberia, she fled – only to be caught in Leningrad. There, she was arrested and sentenced to a further three years in a labour camp. Her act of maternal defiance was met, like so many others, with the full force of Soviet punishment.

In 1951, having completed his schooling in Estonia, the young Rein Vare was arrested once again. He was held for several months in Tallinn’s notorious Patarei prison before being sent back to Siberia. This second deportation marked a breaking point.

Though the Vare family were eventually allowed to return to Estonia in late 1958, they were profoundly changed. Rein Vare, once a hopeful boy who had chronicled his exile with heartbreaking clarity, had become embittered – alienated not only from the regime that had destroyed his family, but from the world itself.

Rein Vare died in the Orwellian year of 1984 in Viljandi. His body was discovered several days after his death, alone and forgotten. Alongside him, his diary – gnawed by rodents but still legible – was found. In time, it was published. Much like Anne Frank’s, Rein’s diary stands as a haunting testament to a stolen childhood and a world deformed by tyranny. Fragile yet enduring, it survived to bear witness where so many voices were silenced.

In 1944, the Red Army reoccupied Estonia, marking the return of Soviet rule. What followed was a renewed wave of repression against the local population, as the regime sought once again to crush any trace of national resistance. Another massive deportation followed a few years later, on 25 March 1949, when over 20,000 people – almost 3 per cent of the Estonian population in 1945 – were seized in a matter of days and sent to remote areas of Siberia.

Read also: Pictures: Deported Estonians in Siberia.

Photos by the Estonian National Museum, the Museum of Occupations and Wikimedia Commons. * This article was first published on 14 June 2014 and lightly edited on 13 June 2025.

Because of high execution and death rate of deported men (only about 7% survival rate) and less than 50% overall survival rate of all deportees, it would not be an exaggeration to lable this as a deportation and execution program.

Yes indeed it’s Genocide of the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Peoples. Mitte Kunagi Enam,Never Again!

I was just six years old when I was told to sit on our living room sofa in Kaupmehe Street in Tallinn and shut up and not move. I have never forgotten how frightened I was. My mothers’ sister one up [Mary Jaansoo, Nõmme] and her family were in the cattle wagons at the Tallinn railway station. She and my favourite cousin Albert were separated from her husband who was the Police Commissioner of Nõmme. Shot ere arrival in Siberia. Yes, we were to meet after . . . in circumstances I still have to believe. Our own pathway to hide in Estonian forests came the next day . . . .at 79 I am one of the lucky ones!

Hi Eha. We are living with our family in your mothers sisters appartment in Nõmme. It would be really interesting for us to hear about Jaansoo’s family. With best regards!

Please write to me as I am related to the Jaansoo family

See on Meie, “Holokaust”, Balti Holokausti Meenutame alati, mäletada ja õppida sellest hirmus kuritegu inimsuse vastu. Need kurjategijad, kes on veel elus olema vahistamise ja kohtu alla ja õiglust tuleks kaotada!

See on ka põhjus, miks eestlased, lätlased ja leedulased peavad ja ei tohiks kunagi toetada jõupingutusi kehtestada Relva Kontroll meid meie endi valitsused, EL ÜRO või mõni teine. Oli Balti riikide vastu, kus relvade Nõukogude Terroristid ajalugu oleks olnud teistsugune. Eestlased lätlased ja leedulased ei oleks loobunud oma vabadusi okupeeriva Terrorist venelased. las see õppetund. Never Again, Relvad Käes, Elagu Eesti Vabariik!

This is our, Holocaust, The Baltic Holocaust, let us Never Forget, Remember and Learn from this horrible Crime Against Humanity. Those perpetrators who are still alive should be arrest and brought to trial and justice should be dispensed!

This is also why Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians must and should Never Support Efforts to enact Gun Control On us from our own governments, the EU UN or any one else. Had the Baltic Nations Resisted with Arms the Soviet Terrorists history would have been different. Estonians Latvians and Lithuanians never should have given up their freedoms to the Occupying Terrorist Soviets. let this a Lesson to be Learned. Never Again, Weapons in hands, Relvad Kaes!

Never forget, never forgive

Mitte Kunagi Enam,Never Again!

If Russia ever tried this again we will fight and kill them, 100% Guaranteed!

A very moving video and article, Iain. I do recall how shocked we were to witness the abandoned homes and articles ,which vividly recounted how children and whole families were lifted from their beds and put on cattle trucks to Siberia when we visited the Country Museum,near Tallinn in 1998. I remember returning to Scotland and asking older friends and family who had served in WW2 how the rest of the world could let this happen, especially the 2nd deportation in 1949. The Estonians are rightfully proud of their history and it is so important that their past struggles are never forgotten.

Muriel x

Another horrid example of mans inhumanity to man, and something I NEVER learned about in HS or college. I pray all those that survived the Estonian Holocaust have had happiness of family and success in their life and their example & strength will assure nothing like this happens to their country again. And with the oncoming tragedy i see in my minds eye, with The Ukraine & Russia, I worry we could see another example of Russia’s ability to rein terror & destruction on it’s neighbor.

Is there any record of the names of the deportees ? I would like to know the fate of some relatives . My grandparents were Estonians and they emigrated to Brazil , but their relatives remained in Estonia , until they disappeared.

http://www.okupatsioon.ee/et/memento-2001/nimekirjad-vahepealsetel-aegadel-kueueditatud

– in this site you found 3 different namelists .

Dear Margot Latt, thank you very much!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LR-gCT3jx80

My grandfather’s family was taken to Siberia from their farms in Valgamaa.My deported family survived . My grandfather’s dad escaped during ww1 and became a merchant sailor, and years later came to live in the Bahamas where I live now.my name is Luke Prosa and i am 11. ( I’m using my grand mothers computer.)

I was only 3 years old in June 1941 and thankfully our family in Nomme was not impacted by the deportation. My grandfather, who was Pastor Kapp of Kaarli Kirik in Tallinn died thankfully in 1940, as he would definitely been deported. Two of my uncles were deported in June 1941 to the Soviet Union. My mother, sister and I escaped from Tallinn in September 1944 and lived in Germany until 1949 when we were allowed to move to the United States.