No products in the cart.

The relations between Hungary and the EU have been rocky, to put it mildly. However, the European capital recently had some good news for Hungary. On June 7th, the Budapest Business Journal reported:

The European Commission will initiate the suspension of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) against Hungary … According to the EC’s assessment, Hungary—taking into account the country’s higher defense spending—has taken effective measures in the interest of ending the EDP

This is good news, because it shows that Brussels and Budapest can ‘get along’ on substantive policy issues. It is also good news because Hungary no longer has to have the Damoclean Sword of the EU’s fiscal wrath hanging over it.

Although nobody in Brussels likes to admit it, the Excessive Deficit Procedure is the very first step that the EU takes if it wants to enforce its Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) against a member state. There is a long journey from an EDP to the extreme anti-deficit measures, founded in the SGP, that Greece was subjected to 15 years ago. It is very unlikely that any EU member state will find itself in the dire ‘Greek’ situation, at least in the near future.

The deficit in the consolidated Hungarian government sector has indeed been significant recently, but a historical comparison shows that it is nowhere as bad as it has been in the past. Figure 1 reports the consolidated public deficit as share of GDP since the turn of the Millennium; the red line marks the 3% of GDP deficit limit that the EU constitutionally requires its member states to comply with.

Figure 1

Although Hungary technically has violated the 3%-of-GDP limit since 2020 and the pandemic, the deficit trend has overall been positive. The deficit has shrunk from 8% to 5% of GDP, with a clear trend toward even smaller deficits. This budget hole is nowhere near as alarming as it was back in the 2000s.

In fact, Hungary joined the EU in 2004 with a consolidated budget deficit in excess of 7% of GDP, and without the positive trend we now see in the nation’s public finances.

Does this suggest that the EU’s Excessive Deficit Procedure against Hungary had some ulterior motive? I don’t think so. The lack of enforcement at one point and the presence of it at another, less severe one, is likely the result of a long-standing EU tradition when it comes to excessive debt and budget deficits: do not follow any particular, predictable method in what countries to pick on and which ones to give a pass.

Generally, the EU has no reason to be concerned about either the Hungarian government’s budget or the country’s economy as a whole. Quite the contrary, in fact: while Europe in general has faced increased economic challenges in the past 15 years, Hungary has stood out as a steady source of GDP growth and sound economic balances.

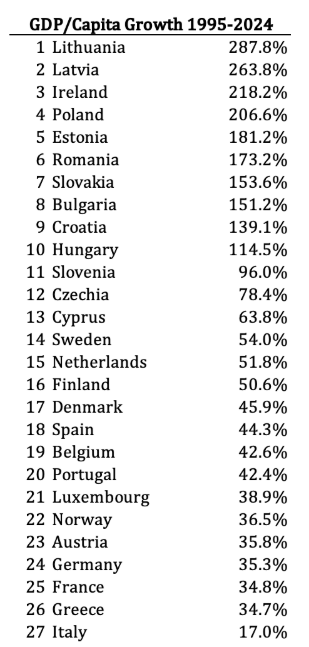

One of the best metrics on the strength of the Hungarian economy is GDP per capita. Over the past 30 years, Hungary has more than doubled its economy per resident (adjusted for inflation), which puts the country in the top ten among the 27 current EU member states:

Table 1

In comparison to the Baltic states and others higher up on the list, the Hungarian number may not seem as impressive. However, with the exception of Poland and Croatia, all the states ranking higher than Hungary have experienced significant volatility in their economies over the past three decades.

Hungary has largely escaped those episodes, which means that the 114.5% improvement in standard of living has emerged from a trend of broad-based, solid economic growth. That growth, in turn, splits up into two distinctly different periods:

In the pre-Fidesz period, from 1995 to 2010, the three Baltic states again topped the chart: Latvia +125%, Lithuania +121%, and Estonia +106%. Hungary came in at 46.5%, which is a solid performance given that the current 27 EU member states only reached 27%.

Under Fidesz, the standard of living of the Hungarian people has continued to improve. Adjusted for inflation, its GDP per capita grew by 46.4% from 2010 through 2024.

At first glance, this looks like a loss compared to pre-Fidesz numbers, but it is actually a remarkable achievement. The Hungarian economy is not an isolated island, but deeply integrated in, and dependent on, the European economy. Therefore, it matters a great deal how the rest of Europe has fared economically.

If we disregard the recession of 2009-2010, here are the salient numbers:

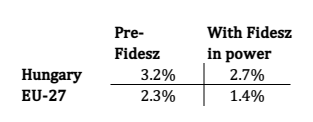

Table 2

Before the 2010 election, the Hungarian economy grew at an inflation-adjusted 3.2% per year, while the 27 current EU member states grew at 2.3%. The Hungarian governments of that time built a respectable economic record, but not an impressive one.

That, on the other hand, happened after Fidesz took over. Although the average annual growth rate is only 2.7%, it is almost twice as high as the average for the EU 27. If the pre-Fidesz governments had done the same, the Hungarian economy would have been growing at about 4.6% per year on their watch.

In other words—and this is important: since 2010, Fidesz has managed to increase the standard of living in Hungary by virtually the same rate as preceding governments did in 1995-2010, but they have done so under much more challenging economic circumstances.

One of the many components of the Fidesz strategy over the last 15 years has been to generate strong, balanced growth in the economy. In the pre-Fidesz era, GDP did indeed grow at respectable rates, and business investments—also known as capital formation—accounted for 20-21% of all economic activity.

However, the trade balance was bad: from 1995 through 2008, Hungary did not have a single year with a trade surplus. There were scattered quarters here and there when exports briefly exceeded imports, but the growth in the economy that previous governments achieved came at the price of long periods of painful trade deficits.

A country like Hungary cannot run trade deficits permanently. It erodes the value of the currency, thereby depreciating wages and hollowing out the value of just about any domestic economic activity. Over the long haul, the only remedy is for the central bank to push interest rates very high—but that only has the effect of making business investments unaffordable and even a modest standard of living unattainable.

The experts that came into office with Viktor Orbán in 2010 laid out a new course for Hungary. They sought to fix the trade deficit by encouraging foreign direct investment—and they were successful. By making Hungary an attractive destination for corporations seeking to build new production capacity, Orbán’s government rapidly improved the trade balance: on his watch, Hungary has only had two quarters of trade deficits, one in 2020 and one in 2021. Both are attributable to the extraordinary economic circumstances of the pandemic.

All in all, the Hungarian economy has performed remarkably well over the past 15 years. Few other countries in Europe are worthy of a comparison: some of them, like Poland, have followed similar economic policy plans, while others, like Ireland, achieve similar growth rates but at the cost of excessive economic instability.

It remains to be seen which path Hungary will choose in the coming years, but any departure from the policies that have underpinned fifteen years of rising prosperity would be a mistake.