Short vignettes of a day in Israel under bombardment.

The routine rushed morning conversation with my daughter and mother of three who lives in Yafo — takes place as she stands in line at the supermarket.

Idele Ross

“Ima, last night, one of the Iranian missiles hit a building in Petach Tikvah, around the block from where S and Y live. Windows in their brand-new apartment jumped their tracks from the impact. Their kids are fine, but Y is terrified,” my daughter reports.

“So, what’s with end-of-year school plans?” I ask in order to change the subject away from such distressing news about friends of my kids.

“Well, the girls are on Zoom in the morning with their teachers, but it’s hard for them to concentrate, and hard for the teachers, too,” she said.

“Kids are missing school and each other,” she added. “The two-day camping trip to the north for the sixth grade has been canceled and D is disappointed. Her Scouts end-of-year sail is postponed as is the sixth-grade graduation party and the play, based on Wicked, the sixth-graders were rehearsing.”

I also know that two of my three granddaughters are part of a Yafo dance ensemble that was to perform at the Israel Festival in Jerusalem. Canceled as well.

“You and your sister grew up during the Intifada — an era of terror attacks, of suicide bombers and buses blowing up. So much death and destruction,” I said. “Then there was the Scud War, when we had to cower in our living rooms or shelters wearing gas masks, and you guys were so much braver than either your Abba or me. There were peace treaties or almost peace treaties along the way, but the conflict and the killing never stopped.

“Now, my grandkids, the third generation of our family, who grew up and into Corona, are the targets of Iranian missile warfare,” I said. “When will Israel find peace?”

Silence.

“I’d like 250 grams of sliced yellow cheese double wrapped, please, and 300 grams of white cheese spread,” I hear my daughter respond. “Gotta go, Ima.”

Recycling

After receiving the all-clear from the Homefront Command, I continue my day, taking old newspapers and a bag of empty plastic containers and bottles to the recycling station near my Jerusalem apartment. Outside the apartment building next door, a Magen David Adom ambulance and a firetruck with flashing lights have parked, but the emergency seems to have been resolved.

The ambulance driver is not going to tell me what happened so I just thanked him for his service as he pulled out to go. Anyway, probably someone got stuck in the saferoom.

Beautiful morning. Empty streets mostly. Kind of a Yom Kippur vibe all around.

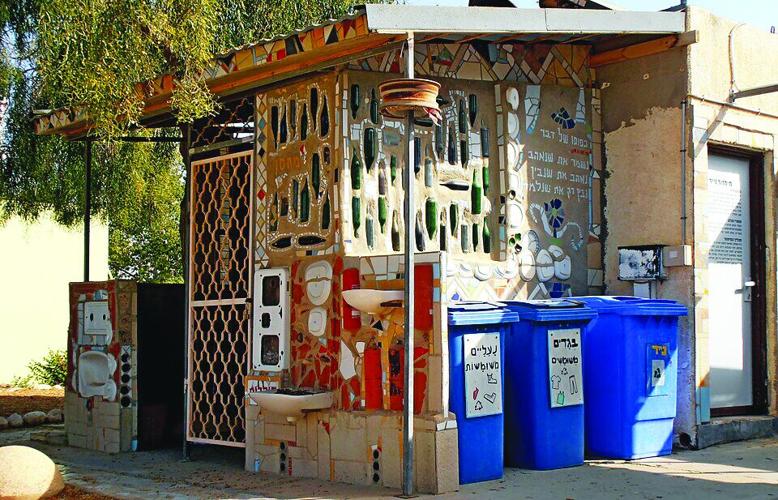

No one but me at the recycling station where the yellow clothes bin is overflowing with people’s hand-me-downs no one is claiming.

A recycling station in Israel

A dirty old car pulls up to the curb as I am tumbling my plastic stuff into the bin. I turn to see the driver, a 50-something-year-old guy with a car full of plastic and glass bottles. He extracts himself from his vehicle with great difficulty, using his crutches to leverage himself out onto the asphalt.

“Do you have bottles?” he asked me.

“At home” I say. “I didn’t bring them.”

“Do you live near here? I can pick them up,” he offers.

“Not worth your effort,” I say. “It’s only a few.”

“This is my livelihood, how I feed my family,” he explains.

Using one of his crutches to poke through the purple bottle recycling bin, he pulls a few glass and plastic bottles out, each one bringing a deposit of 30 agarot (very roughly about 10 cents) and tosses them onto the floor of his car through the open window.

Then he pauses, looks at me stuffing my old newspapers into the already full green paper bin.

“You and I, we have no trouble getting along,” he says. “It’s the crap leadership, yours and ours. All they care about is power and money.”

Then he swears in Arabic.

“Majnoun,” I say. (“Crazy” in Arabic. One of the 10 useful words I know.)

“Meshugah,” he replies with a sad smile.

I want to say Salaam to him as I leave, but I can’t bring myself to form the word and release it into the world. It seems flat and forced, empty of meaning.

Nonetheless, we wish each other well, and I walk home empty-handed.

The Conversation

A gentle midafternoon breeze comes through my shaded bedroom window as I lay on my bed reading a book. My phone rings. It’s a video WhatsApp call from my Chicago friend Marty, whom I met on a kibbutz 50 years ago. Despite his leaving Israel after six years, he has maintained close family-like friendships with people he met on the kibbutz and one of them is me.

“Oof, I look terrible,” I exclaim. “I hate video calls.”

“I wanted to check in and see how you are doing. It’s dark on my side. I can barely see you,” he reassures me.

He does most of the talking, wanting to share the success of his meetings with groups, churches, synagogues and high school students during which he tells the extraordinary story of his parents, Nana and Aunt … all Holocaust survivors.

His parents had lived in pre-state Palestine, served in the Haganah and eventually, against their wishes, he resettled in the U.S. But Israel and Zionism were always part of the family conversation. He is proud of the impact he believes he is having on youngsters through the talks he gives and the conversations that take place afterward.

“I’m also involved with the Wiesenthal Center and am having dinner this evening with the Midwest director,” who took him on as a speaker he tells me proudly.

We haven’t spoken since his trip to Poland.

“Auschwitz Birkenau was so touristy that I found it sterile and not as powerful an experience as I was hoping.”

I told him how some years ago, I had completed a course at Yad Vashem to be a guide for March of the Living. We had a five-day educational tour of Poland. I told him that I found the power and the horror in small moments, in the unexpected: like the one red open-toed sandal on the heap of shoes at Auschwitz; the dirty looks we encountered from Poles on the streets of Warsaw who seemed to understand we were speaking Hebrew, the apartment complex very close to a Holocaust memorial site in Warsaw surely built on the bones of dead Jews. I felt ghosts.

He yearns to be here with his people in their time of need. He regrets that he left and never served in the army when he could have. He lets it all out with me.

His pain, his fear of the peril we are facing, understanding that all the pro-Israel activity there in Chicago is no substitute for being here, on a kibbutz volunteering or in Jerusalem having a barbecue with his longtime friends and sharing the sirens huddling in our saferooms, while the chicken wings burn on the charcoals.

He suddenly bursts out crying.

“I’m sorry,” he apologizes, taking his glasses off to wipe the tears away, sitting in the kitchen of his Skokie condominium. “I haven’t cried like this in a while.”

I get it. He is a second-generation son. He tells his parents’ story over and over again and misses them.

He is married to a woman he adores, and they have a wonderful life together. She doesn’t share his passion for Israel, but she understands him and supports him. He is thrilled that Renie, his daughter, a therapist, is right there with him. With her, he shares his grief and concern because she has been to Israel and to his kibbutz several times and loves this country almost as much as he does.

So, he cries, and I hear him, his pain, his longing, his regret for the road not taken.

All I say to him is “Marty, it’s been a long time since I made a man cry.”

He starts to laugh and frankly so do I.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.